The Melody of Love

This companion site complements the published volume Richard Rolle’s Melody of Love by Andrew Albin. In the book, you will find a comprehensive study opening manifold pathways into the Melos amoris alongside the first translation of the text into English, in alliterative prose that mirrors that of the Latin original. The book also contains a series of five appendices, offering an edition of a spurious chapter, marginalia and music found in one key manuscript, reconstructions of early fourteenth-century Anglo-Latin songs and recitations, and guidance through Rolle’s unusual Latin vocabulary. The materials below serve to enhance these supplementary materials with a range of multimedia resources, and seek to open additional pathways into Rolle’s difficult text through an appeal to senses and media that the printed page cannot as easily access.

1. The Translation

As the final section of the study in Richard Rolle’s Melody of Love describes in greater detail, every effort has been made to prepare an Englished Melos amoris that practices Rolle’s distinctive alliterative prose style, while still rendering a translation that accurately represents the contents of the Latin text. Naturally, pursuit of these dual aims presents significant challenges: a balance must be struck between them, achievable only through a resourceful approach to and considered interrogation of equivalence in translation. Translation studies in the wake of the writings of Walter Benjamin have helped loosen the received virtue of to-the-letter accuracy, traditionally conceived; theories of mouvance and research in material philology suggest other virtues more native to medieval manuscript culture that translation might productively adopt. Embrace of stylistic fidelity has had the salutary effect of locating the translated Melody of Love within a heritage of medieval textualities: like a garment hugging a body, the English rendering slips against its Latin original, its fit variably loose or tight, to render one more shifting – and shifty – iteration of Rolle’s work. My hope is that both the smoothnesses and irritations of this approach prove generative to readers, students and scholars alike.

Here, you will find a short excerpt from the published translation, taken from the most alliteratively dense section of the Melos amoris. Chapter 16 picks up midway through Rolle’s exegesis of Psalm 21:15, “My heart’s become like wax melting in the midst of my bowels,” which the hermit takes as a reference to the spiritual sensations for which he was and is so well known. The ensuing chapters elaborate on these sensations, on the form of living they demand, and on the fate of those who refuse their pursuit in favor of worldly delights. The numbers running along the outer margin of the text indicate corresponding page numbers from the Latin edition of Rolle’s text: The Melos Amoris of Richard Rolle of Hampole, ed. E.J.F. Arnould (Oxford, 1957). Eventually, we expect to make the entire translation available here, for wider pedagogical access.

2. The Manuscript

The Melos amoris survives in ten manuscripts containing all or major portions of the text, plus nine fragments and a partial medieval glossary of difficult Latin terms. Of the ten major manuscripts, one is especially deserving of special attention: Lincoln College MS Latin 89, which contains a grossly imperfect, marginalia-filled copy of the Melos and a gathering of mid-fifteenth century music notation, an unusual pairing that has gone uncommented upon until now. Appendix 2 of Richard Rolle’s Melody of Love offers transcriptions and translations of the narrative glosses in the Lincoln manuscript, but these discursive marginal additions hardly exhaust the manuscript’s fascinating scribal contents. Its folios are full of interlinear and lexical glosses, underlining, notae, maniculae, and other scribal marks that, attended carefully, shed significant light on what late-fourteenth/early-fifteenth century readers of the Melos amoris found worthy of comment.

Some codicological features of the Lincoln manuscript's Melos deserve preliminary comment. Dated to the late fourteenth or early fifteenth century based on watermarks and the English cursive hand, this portion of the manuscript is copied on rag paper folios measuring approximately 30x22cm that have suffered varying degrees of damage along the outer margin. Much of the marginalia appears to be in the same hand that copied the main text, itself the work of a single scribe copying at intervals (breaks in copying are especially noticeable on fols. 2vb, 3vb, 9ra, 13va, 14ra, 19rb, 21rb). A taller, crisper anglicana script authors some of the notae and perhaps their accompanying maniculae; a separate hand may be responsible for the medical glosses on fols. 1r and 3r, though it resembles the main scribal hand in most points.

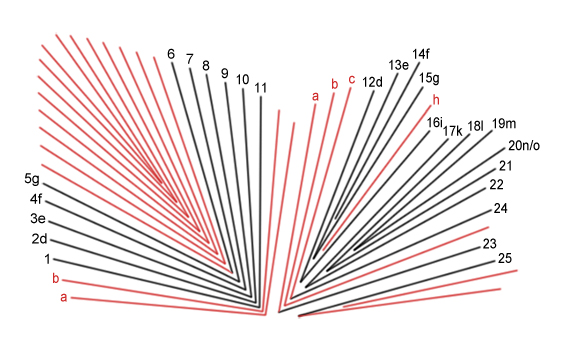

The manuscript’s present collation is as follows: I¹² (lacking 6), II⁶ (lacking 5), III⁶, IV¹, V¹, VI¹. Quire markings appear intermittently, centered near the top edge of the recto, in two alphabetic sequences: d through g on fols. 2–5, and d through n/o, lacking h, on fols. 12–20. Narrative glosses wrap around these quire markings at the top of fols. 16r, 18r, and 19r, indicating that marginalia was added after the quire markings were already in place. The imperfect textual witness is distributed as follows, in agreement with the present collation, always beginning and ending mid-chapter: chapters 4–11 (fols. 1r–5v); chapters 24–32 (fols. 6r–11v); chapters 38–43 (fols. 12r–15v); chapters 45–52 (fols. 16r–22v); chapters 55–56 (fols. 23r–23v); chapters 52–53 (fols 24r–24v); chapters 56–57 (fols. 25r–25v). Based on word count and textblock density, we can readily estimate how many folios would be required for the lacking text. Taken as a whole, this data allows us to reconstruct a hypothetical original collation as follows:

Some features of the scribe’s work also bear comment. It appears that, as he copied the main textblock, the scribe left blank space for individual words to be filled in later, perhaps because of uncertain readings in his exemplar. These omissions are customarily marked with marginal ° symbols, with the missing words written in after the main textblock was completed. Sometimes the later addition is noticeable because of contrasting ink color; omissions that the scribe neglected to fill in can be found on fol. 6v and 19r. Reminiscent of the partial glossary of uerba difficilia found in Cambridge University Library MS Dd.5.64, fols. 84r–84v, unusual and important words in both textual columns are usually glossed along the outer margin, occasionally in line. Rolle’s more obscure terms sometimes go misspelled, as “palidonias” for palinodias on fol. 16v. The scribe’s medieval Latin orthography is consistent: “cunta” for cuncta, “inmundus” for immundus, “silicet” for scilicet, “cahos” for chaos, etc. His in usually takes the accusative where Arnould has ablative; his pointing is sparse and somewhat idiosyncratic.

In the semidiplomatic transcription here, I have aimed to reproduce the look and layout of the manuscript page as closely as possible. No distinction is made between round and tall s, or between r and r rotunda; distinction is made between u and v. I have attempted to reproduce finding marks with similar typographical glyphs and seek to represent crossouts, subpunction, and inkblots as they appear. I expand abbreviations in italics and enclose brief superlinear insertions between slashes, / . Where damage to the manuscript makes readings difficult or impossible, especially in the final three folios, I indicate conjectural readings or lacunae between square brackets, [ ].

Lincoln College MS Latin 89, fols. 1–25

3. The Music

Appendix Three of Richard Rolle’s Melody of Love accounts for Lincoln College MS Latin 89 fols. 26–31, a gathering of fifteenth-century sacred English music bound together with the manuscript’s imperfect, densely annotated copy of the Melos amoris at some point before the seventeenth century. In the Appendix, Andrew Albin offers commentary on the gathering in its manuscript context, while Bryan Martin assesses the gathering’s contents from a musicological perspective. Martin also prepares scores in modern notation for all musical works in MS Latin 89 that are preserved in toto or can be completed with the help of concordances.

A handful of errors appear in these scores. Corrections are as follows:

- p. 387, m. 59: the notated E should be D

- p. 390, m. 4, middle voice: the indication of coloration at the beginning of the measure is an editorial correction to the MS, in which the two semibreves of m. 3 are also colored

- p. 395, m. 30, top voice: the notated F should be E

- p. 395, m. 38, bottom voice: the notated F should be G a step down from the preceding A

- p. 398, m. 44, top voice: the notated G is editorially supplied, replacing a semibreve rest in MS

- p. 400, m. 46, bottom voice: the typographic indication of coloration is misplaced to lie adjacent to the bottom of the middle staff

Practical though these scores are for critical analysis and performance, the rendering of MS Latin 89’s music in modern notation obscures important scribal aspects of interest to musicologists. Martin and Albin have therefore prepared a semidiplomatic transcription of the music gathering, rendering the white mensural notation that appears in manuscript in a format that will aid researchers who seek to return to the original. As opposed to the scores found in Richard Rolle’s Melody of Love, these scores only represent the music on the folia of MS Latin 89. Where damage has made notation illegible or irrecoverable, we have used the same concordances as the modern scores of Appendix Three to supply missing material in tall square brackets. Otherwise, material from concordances has been excluded, leaving voice parts and musical works incomplete where they appear so in MS Latin 89.

Further editorial intervention has been restricted to the following: compositions are presented in score, even when written in parts in manuscript; ligatures are broken into their constituent notes and marked with horizontal brackets above the staff; dots of division float between notes to distinguish them from dots of addition, which appear adjacent to the note they affect; and missing text is indicated in italics without speculation about underlay. Scribal errors of transposition, coloration, and mensuration have not been corrected. We have taken a conservative approach to dots of addition and division, for which stray ink marks or irregularities in the material composition of the paper folio can be mistaken. The musical jottings on fol. 27v and 31v, and the small surviving fragment of ?Orbis factor on fol. 30 have not been included.

Lincoln College MS Latin 89, fols. 26–31

High-quality, full-color scans of these MS Latin 89’s music gathering are available at the Digital Image Archive of Medieval Music (free registration required) as GB-Olc MS Lat. 89. DIAMM entries for the concordances listed on p. 381 of Richard Rolle’s Melody of Love are as follows:

Beata mater

Man assay

- GB-Ob MS. Arch. Selden B. 26

- GB-Lbl Add. MS 5665

- GB-Obac MS 354 (no DIAMM entry)

Kyrie (fol. 28r)

Descendi in ortum meum

Kyrie Lux et origo

4. The Recordings

As sophisticated a literary project as it is, the Melos amoris is also a playful work of late medieval English sound art, as committed to the confection of its phonics as to the profundities of its doctrine. The Melos’s appeal to the ear is all the more audible in the Lincoln manuscript, whose pairing of Rolle’s mystical text with music notation invites us to encounter the work in the fullness of its sounded dimension.

The recordings below aim to make that sounded dimension more readily available to modern readers and audiences. They recreate a program of Latin recitations from the Melos amoris and songs from the Lincoln manuscript originally performed on February 26, 2016 at St Thomas’s Anglican Church, Toronto as part of Sine Nomine’s 2015–2016 concert season, and again on April 12, 2016 at Christ Church, New Haven as part of Yale University’s Institute of Sacred Music concert series. Here, Andrew Albin recites excerpts from the Melos using reconstructed early fourteenth-century Anglo-Latin pronunciation; Sine Nomine performs the music, with Andrea Budgey (voice, rebec, and harp), Janice Kerkkamp (voice), Bryan Martin (voice and lute), Randall Rosenfeld (gittern and voice), and David Roth (voice). The performance was recorded on May 30, 2016 at the Church of St Mary Magdalene, Toronto, with Richard Hess as audio engineer.

Texts and translations may be found in Appendix 4 of Richard Rolle’s Melody of Love. To listen to the full program, click here: Melos amoris: Music from a Mystical Manuscript

For individual tracks, see the listing underneath:

- 1 Chapter 9: Splendid and sullied souls

- 2 Man assay (fol 27v)

- 3 Chapter 18: I've put off the planet's pabulum

- 4 Kyrie (fol 28v)

- 5 Chapter 21: The Word woos and rewards

- 6 Beata mater (fol 27r)

- 7 Chapter 17a: I proclaim the prize of Paradise

- 8 Kyrie (fol 29r)

- 9 Chapter 14a: Let us heed our death day

- 10 Descendi in ortum meum (fol 29v)

- 11 Chapter 17b: The fate of the false faithful

- 12 Chapter 14b: Saints spurn secular swill

- 13 Rex virginum amator Deus (fol 31r-31v)

- 14 Chapter 48: We burlesque in the bed of invisible bliss

- 15 Kyrie (fol 28r)

- 16 Chapter 20: What happens to hellbound hypocrites

- 17 Chapter 15: The solitary swept up to supernal song

- 18 Gloria in excelsis (fol 27v) (intabulation)

- 19 Chapter 30: Meditation on the passion

- 20 Lux et origo (fol 31v)

Page last updated 16 May 2019