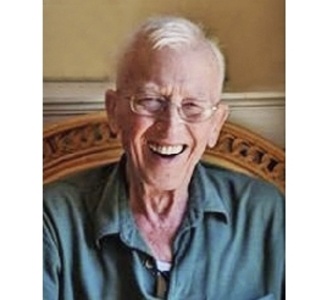

A.G. Rigg (1937–2019)

Honorary Fellow, Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies

In memoriam

Arthur George Rigg was born on 17 February 1937 at Wigan (Roman Coccium), a town in northwestern England, near Manchester. Between 1959 and 1966 he received his B.A., M.A., and D.Phil. at Oxford. His thesis, “An Edition of a Fifteenth-Century Commonplace Book,” was written at Merton College under the supervision of Norman Davis, the successor of J. R. R. Tolkien in the position of Merton Professor of English Language and Literature. This work, published two years later as A Glastonbury Miscellany of the Fifteenth Century: A Descriptive Index of Trinity College, Cambridge, MS O.9.38 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968), both displays George’s philological acumen and maps the main areas of his scholarly interests: Latin and Middle English philology, manuscript studies and critical editing, medieval poetry and literary history. It was an auspicious beginning.

Amid finishing his thesis and teaching at various Oxford colleges, George met his future wife Jennifer, and the two registered their marriage on 3 July 1964. As legend has it, before going to the magistrate Jennifer and George went to the pub, and this seems to have been the only time he could not finish his beer. The couple left for the New World in 1966 when George was appointed Visiting Assistant Professor of English at Stanford University. They travelled in style on a transatlantic liner, as one did in those days, and arrived in San Francisco after two weeks of exciting journey through the Caribbean, the Panama Canal, and under the Golden Gate. They spent two years at Stanford—including hours, even days, in intertidal pools along the wonderful nearby Pacific shore—before moving to Canada when George took up the position of Associate Professor at the newly formed Centre for Medieval Studies (CMS) at the University of Toronto. He remained at this institution for the rest of his academic career, receiving an early promotion to full professorship in 1976, a year during which he also served as Acting Director of the Centre, and a reluctant retirement in 2002.

Upon his arrival at CMS, George dedicated himself to two initiatives that established Toronto’s fame as one of the best academic environments for learning and studying medieval Latin in North America. Both initiatives were undertaken in close collaboration with the academic staff at the Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies (PIMS). The first had to do with inaugurating a new Latin programme, comprising two different levels, M.A. and Ph.D., for the benefit of the students at both PIMS and CMS. A Latin committee was created to examine the translations of the students, who could write the exams twice a year, and to formulate the criteria for “pass” or “fail” that would ensure that a student from Toronto was able to pursue original research anywhere in the world. From its inception until his retirement, George chaired the Latin committee almost uninterruptedly and taught the M.A. and Ph.D. Latin courses in alternate years. The rigorous Latin standards established by him make the Toronto Latin programme unique, and it continues to provide a great service to the field of Medieval Studies to the present day.

The second initiative was related to the important Toronto Medieval Latin Texts series (TMLT). The series was launched in 1972, and both Father James P. Morro, the then-director of publications at PIMS, and Father Lawrence K. Shook, the Institute’s Praeses, supported the project whole-heartedly. This collaboration is ongoing, since the series is still published by PIMS on behalf of CMS. During George’s editorship between 1972 and 2008, thirty volumes were printed, including his own A Book of British Kings: 1200 BC–1399 AD appearing as vol. 26 in 2000. The idea behind the series was to provide students and instructors with affordable editions (a volume in those days could be purchased for $3.75) of representative Latin texts which were based on single carefully selected manuscripts and which also included copious notes for the student. The aim was not to produce critical editions but to capture a particular moment in the transmission of the work with its distinctive scribal and utilitarian peculiarities. In this approach the TMLT series was ahead of its time and thus provoked mixed reactions, especially from classicists, as can be seen in the debate between George and John Barrie Hall in the journal Studi medievali, 3rd ser., 24 (1983). This significant moment in the history of textual criticism as applied to medieval texts continues to be invoked in the contemporary scholarly literature.

George’s list of publications is impressive. In the 1970s and 80s, he published three volumes in the PIMS series Studies and Texts: The Poems of Walter of Wimborne (1978); William Langland: Piers Plowman, the Z-version (1983, with Charlotte Brewer); and Gawain on Marriage: The Textual Tradition of the ‘De coniuge non ducenda’, with a Critical Edition and Translation (1986), while simultaneously working on his seminal A History of Anglo-Latin Literature 1066-1422, published by Cambridge University Press in 1992. For anyone who works in the field, George’s History is a treasure trove of information on known and obscure texts, manuscript contexts and lines of reception, historical facts, and cultural significance. The volume also contains countless beautiful and witty translations of medieval Latin poetry into modern English verse. George’s talent in this area is displayed in many of his publications but especially in his article “Lawrence of Durham: Dialogues and Easter Poem. A Verse Translation,” The Journal of Medieval Latin 7 (1997) and John Gower, Poems on Contemporary Events: The ‘Visio Anglie’ (1381) and ‘Cronica tripertita’ (1400), ed. David R. Carlson (Toronto: PIMS, 2011). His verse translation of Joseph of Exeter’s Iliad, posted on the website of CMS in 2005, is freely available for downloading.

In addition to his book-length projects, George authored over sixty articles in books or leading academic journals such as Latomus, Medium Aevum, Mittellateinisches Jahrbuch, Speculum, Studi medievali, The Journal of Medieval Latin, and Traditio. Between 1968 and 2003, he published ten articles in the pages of this journal examining topics such as Latin poems against the friars (Mediaeval Studies 30, 1968), the biblical epigrams of Hildebert of Le Mans (Mediaeval Studies 47, 1985), and Henry of Huntingdon’s Herbal (Mediaeval Studies 65, 2003). Still, George’s most important contribution in this context should be seen in his series of articles on medieval Latin poetic anthologies (Mediaeval Studies 39, 40, 41, 43, and, in collaboration with David Townsend, 49), a series which was continued by Peter Binkley (Mediaeval Studies 52, 1990) and Greti Dinkova-Bruun (Mediaeval Studies 64, 2002). As with the TMLT, George’s work in these articles was groundbreaking. His careful examination of a number of poetic anthologies found in manuscripts preserved in the main British libraries drew the attention of scholars to these literary constructs whose dynamic nature constitutes an important expression of specific literary tastes and particular reading habits. We now talk about the medieval anthologizing impulse and the meaning of miscellaneity, concepts which George anticipated, even though never theorized. Thus, it is no exaggeration to posit that George’s scholarly work has shaped the field of medieval Anglo-Latin literature by opening up new avenues for research and by providing the basis for new insights.

It is remarkable to see in George’s case that such a brilliant scholarly activity was combined with an equally successful career as a teacher and mentor. In the course of years, George had the satisfaction of seeing his supervisees spread and populate this continent. During his tenure at CMS he supervised no less than thirty-two academic theses—twenty-four in Latin and eight in Old and Middle English—and his former students can be found at universities from Texas to upstate New York, and from Toronto to British Columbia.

George’s merits in keeping a high standard of Latinity among the medievalists in North America as well as his extraordinary scholarly achievements were appropriately recognized by the Medieval Academy of America and the Royal Society of Canada, which elected him Fellow in 1997 and 1998 respectively. He was also awarded an Honorary Doctorate from the Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies in 2005. In addition, George was the recipient of two Festschriften by his grateful students and colleagues, the first published in 2001 (Anglo-Latin and Its Heritage. Essays in Honour of A.G. Rigg on His 64th Birthday, ed. Siân Echard and Gernot R. Wieland) and the second in 2004 (Interstices: Studies in Middle English and Anglo-Latin Texts in Honour of A.G. Rigg, ed. Richard Firth Green and Linne R. Mooney).

Despite everything that has been said so far, there are more sides to George which I have not touched upon. He was an avid gardener and unrepentant smoker, an organizer of Latin Scrabble tournaments and a science fantasy writer, a staunch royalist and a lover of cats, dogs, and donkeys, a very witty but also a very private man. While I was his student, he never missed a class, and he never was late for a meeting—one of those many meetings to which he always generously agreed—and, as far as I know, George was never absent from an event that was related to one of his students. He was, however, reticent about personal honours and was always absent when he had to receive any of them. He belonged to a generation, or to a kind of man, for whom worldly glory was nothing, while the feeling that one has given one’s very best was everything: memoria nostri durabit, si vita meruimus, to cite Pliny the Younger’s friend Frontinus. Indeed, George Rigg gave his very best to Medieval Studies and to Medieval Latin, and this amounts to no little achievement. He will be dearly missed.

GRETI DINKOVA-BRUUN

Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies

Source

This memorial notice originally appeared in Mediaeval Studies 80 (2018): v–viii. © Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies.