Johannes Scottus Eriugena: Periphyseon

Videsne igitur quantum generalior est Bonitas quam Essentia?

Videsne igitur Locum Tempusque ante omnia quae sunt intelligi?

Videsne igitur senariam humanae naturae discretionem?

Videsne igitur quomodo omnium substantiarum diuisio in humana natura terminatur?

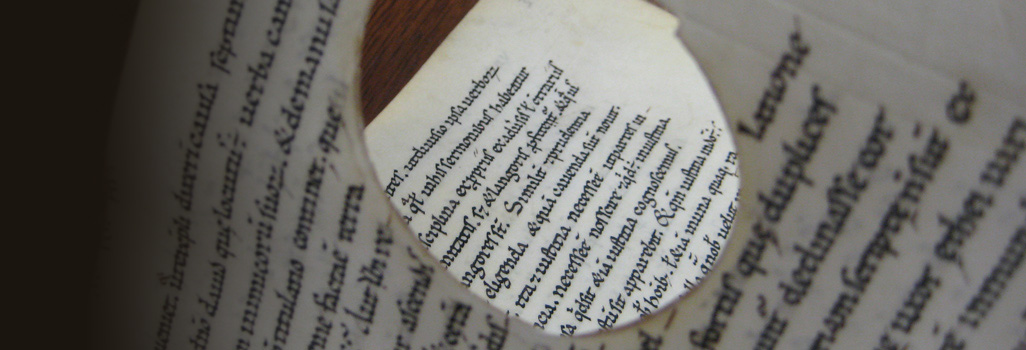

Periphyseon, Liber III, ed. Édouard Jeauneau (Turnhout, 1999), facing p. xxxii

The Periphyseon: Text and Transmission

Yet the most urgent task, and the most difficult, remained the edition of the Periphyseon. One of the difficulties derives from the fact that the manuscripts of Eriugena’s master work present differences that cannot be accounted for by accidents of transcription alone. Everywhere the text shows clear signs of revision. But who made these alterations? The author himself? Copyists acting under his orders? Or ‘editors’ perhaps driven more by zeal than scruple?

Hope for an answer to these questions dawned in 1906, when Ludwig Traube announced that he had discovered annotations in Irish script in the margins of manuscripts of Eriugena’s works, and in 1920, Edward K. Rand, one of Traube’s students, was able to show that these alterations were to be attributed to two Irish hands, which he denominated i 1 and i 2.

Rand was convinced that neither of these hands belonged to Eriugena. This conclusion was contested, however, by two eminent palaeographers, Bernard Bischoff and T.A.M. Bishop. Detailed investigation of the two Irish hands led Bishop in 1975 to announce two conclusions: that one of the two hands (i 2), was certainly not that of Eriugena, while the other (i 1) was most likely his. These conclusions were given definitive shape by Édouard Jeauneau and his collaborator Paul Dutton in their comprehensive and intensive study of the two hands in The Autograph of Eriugena (Turnhout: Brepols, 1996).

The first of Bishop’s conclusions is of cardinal importance: if it is incontrovertible that i 2 is not the author of the Periphyseon, it is nonetheless obvious that his hand intervened in the text, adding to, excising from, and modifying it, often in rather cavalier fashion. Other revisions, no more authoritative than those of i 2, have followed.

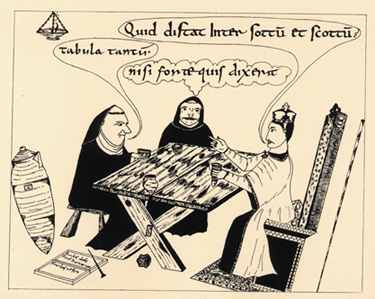

The importance of i 2 in the transmission of the text is playfully depicted in the picture below.

Conceived and executed by Randall Rosenfeld, co-director of Sine nomine, this cartoon illustrates an anecdote reported by William of Malmesbury (†1143) and most probably invented by him. King Charles the Bald and John the Scot (Eriugena) were seated at the same table, when the latter did “something” which offended good Gallic manners (quod Gallicanam comitatem offendebat). Thereupon the King said: “What separates a Sot from a Scot?” To which John answered: “Only a table.”

Between the two protagonists is seated a disciple of John, also an Irishman, who played an important role in the diffusion of the Periphyseon. Until now this disciple remained anonymous and, as we have seen, was referred to only by the siglum of his hand, i 2. Recently, it has been suggested that he be called Nisifortinus, for he introduces some of his corrections by the polite formula Nisi forte quis dixerit — corrections, we might add, that tend generally to make Eriugena’s bolder claims more ‘orthodox.’

Although cartoons are meant to amuse and delight, and not to reproduce historical fact with singleminded zeal, Randall has nevertheless created an instructive picture that draws its inspiration from several medieval details. The twelfth-century monastic habit worn by Charles’ two interlocutors, for example, shows the origins of the anecdote in a Benedictine abbey more than two hundred years after the death of Eriugena. The lamp hanging over John the Scot, the throne on which the king is seated, and the king himself are all based on an illustration from the First Bible of Charles the Bald (Paris, BnF lat. 1, fol. 423v). Moreover, the words pronounced by the king’s two guests are written, appropriately enough, in Irish script: Eriugena’s reply in the hand of i 1, Nisifortinus’ remark in the hand of i 2. And on the floor, lies a wax tablet bearing the first draft of a drinking song attributed to the author of the Periphyseon: “Bacchus is absent; the throats of the Irish are dry.”

The New Edition

The results of the paleographical research sketched above demanded a new style of edition. The Periphyseon appears to us as a work in flux, constantly revised, corrected, and amplified. Since it is impossible to offer, as it were, a complete ‘reel’ of the text, the editor has chosen to provide several ‘frames’ that correspond to the various versions through which it has come down to us. These versions are presented synoptically, so that the reader may easily follow the evolution of the text, if not in all of its details, at least in its significant stages.

Yet in the case of a literary masterpiece such as the Periphyseon, synoptic tables may seem to fall short of what is expected from a standard critical edition. Readers require, and rightfully so, a single, authentic, authoritative text, that can be quoted and cited by all without confusion. The new edition has sought to take into account both these demands. It consists of two parts: the first contains a text embodying, as closely as possible, the ideal defined above; the second offers the various versions in four separate columns (synopsis uersionum).

The new edition also attempts to take into account other features of the text and its transmission. Among the alterations the author of the Periphyseon introduced into his own text are marginalia designed to clarify, complement or comment on passages deemed especially difficult or important. These notes are certainly authentic, no less authentic than the footnotes and endnotes with which a scholar nowadays enriches his or her own books and articles. As early as the end of the ninth century, these marginal notes were integrated into the text of the Periphyseon. The result is that a subject was sometimes separated from its verb, or a verb from its complement, by ten, fifteen or twenty lines of commentary. The intrusion of the margin into the middle of the page no longer allows modern readers to appreciate fully the literary quality of the Eriugenian dialogue, and even, in some instances, prevents them from grasping clearly the logical steps of philosophical arguments, as they are interspersed with commentaries. In the new edition of the Periphyseon, the intruders, namely the marginal notes, have been returned to their proper place: they have made their way back to their natural element, the margin.

This feature of the new edition is bold and may surprise, even shock some readers. The editor justifies his decision as follows: “I have attempted to make a reality perceptible which up until now was obvious only to those with access to the manuscripts. The dialogue has not reached us as a finished product, but rather as a work in progress, like molten metal, which, today still, after more than eleven centuries, we have the privilege to see as it takes shape between the fingers of an expert goldsmith, Johnannes Scottus Eriugena.”

The Editorial Team

The new edition of the Periphyseon has been prepared by Édouard Jeauneau and an équipe drawn from students of the Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies and of the Centre for Medieval Studies in Toronto over several years. The project has received generous support from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada since 1986. Édouard Jeauneau (S.T.L, Pontifical Gregorian University; D. ès Lett., Paris) is Directeur de recherche honoraire at the CNRS, Paris, and Institute Professor at the Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. His many essays on Eriugena and his work, collected in Études érigéniennes (Collection des Études Augustiniennes: Moyen-Age et Temps Moderne 18 [1987]), won the Prix Victor Cousin for 1990.

Publications

The edition of the Periphyseon for the Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis has appeared at a relatively swift pace: Book 1 appeared in 1996; the concluding volume, containing Book 5, in 2003. For information on ordering, please contact Brepols Publishers.

Iohannes Scottus Eriugena. Periphyseon. Ed. Édouard Jeauneau.

Liber primus. Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis 161. xc, 462 pages. Turnhout: Brepols, 1996. ISBN 2–503–04281–3 (hardbound); ISBN 2–503–04282–1 (paperback).Liber secundus. Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis 162. xiv, 520 pages. Turnhout: Brepols, 1997. ISBN 2–503–04621–5 (hardback); ISBN 2–503–04622–3 (paperback).

Liber tertius. Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis 163. xl, 695 pages. Turnhout: Brepols, 1999. ISBN 2–503–04631–2 (hardback); ISBN 2–503–04632–0 (paperback).

Liber quartus. Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis 164. lxx, 666 pages. Turnhout: Brepols, 2000. ISBN 2–503–04641–X (hardback); ISBN 2–503–04642–8 (paperback).

Liber quintus. Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis 165. xxxiv, 958 pages. Turnhout: Brepols, 2003. ISBN 2–503–046541–7 (hardback).

Édouard Jeauneau and Paul Edward Dutton. The Autograph of Eriugena. Autographa Medii Aeui 3. 224 pages, 99 plates. Turnhout: Brepols, 1996. ISBN 2–503–50542–2 (hardback); ISBN 2–503–50543–0 (paperback).

Other works

Other works by Eriugena have been published in the Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis series, including Eriugena’s commentary on the Celestial Hierarchy of Pseudo-Dionysius, his De praedestinatione, and his homily and commentary on the Gospel of St John. His translations of Maximus the Confessor's Ambigua ad Iohannem and the Quaestiones ad Thalassium appeared in the Greek series of the Corpus in 1988 and 1990 respectively. Copies of these works are available from Brepols Publishers.

Iohannes Scottus Eriugena. Expositiones in hierarchiam caelestem. Ed. Jeanne Barbet. Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis 31. liv, 368 pages. Turnhout: Brepols, 1975. ISBN 2–503–03311–3 (hardback); ISBN 2–503–03312–1 (paperback).

Iohannes Scottus Eriugena. De diuina praedestinatione. Ed. Goulven Madec. xix, 278 pages. Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis 50. Turnhout: Brepols, 1978. ISBN 2–503–03501–9 (hardback); ISBN 2–503–03502–7 (paperback).

Iohannes Scottus Eriugena. Homilia super “In principio erat verbum”; et Commentarius in Evangelium Iohannis. Ed. Édouard Jeauneau and Andrew J. Hicks. Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis 166. Turnhout: Brepols, 2008. ISBN 978–2–503–52914–1 (hardback).

Maximus Confessor. Quaestiones ad Thalassium I. Quaestiones I–LV una cum latina interpretatione Iohannis Scotti Eriugenae. Ed. Carl Laga & Carlos Steel. Corpus Christianorum Series Graeca 7. cxvii, 555 pages. Turnhout: Brepols, 1980. ISBN 2–503–40071–X (hardback); ISBN 2–503–40072–8 (paperback).

Maximus Confessor. Quaestiones ad Thalassium II. Quaestiones LVI–LXV una cum latina interpretatione Iohannis Scotti Eriugenae. Ed. Carl Laga & Carlos Steel. Corpus Christianorum Series Graeca 22. lx, 362 pages. Turnhout: Brepols, 1990. ISBN 2–503–40221–6 (hardback); ISBN 2–503–40222–4 (paperback).

Maximus Confessor. Ambigua ad Iohannem. Latina interpretatio Iohannis Scotti Eriugenae. Ed. Édouard Jeauneau. Corpus Christianorum Series Graeca 18. lxxxiii, 324 pages. Turnhout: Brepols, 1988. ISBN 2–503–40181–3 (hardback); ISBN 2–503–40182–1 (paperback).