Research Seminar. Christopher Lakey: “The Invention of Rilievo: Relief and The Sculptural Imagination in the Middle Ages.”

Mellon Fellow, Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies.

Research Seminar.

Abstract

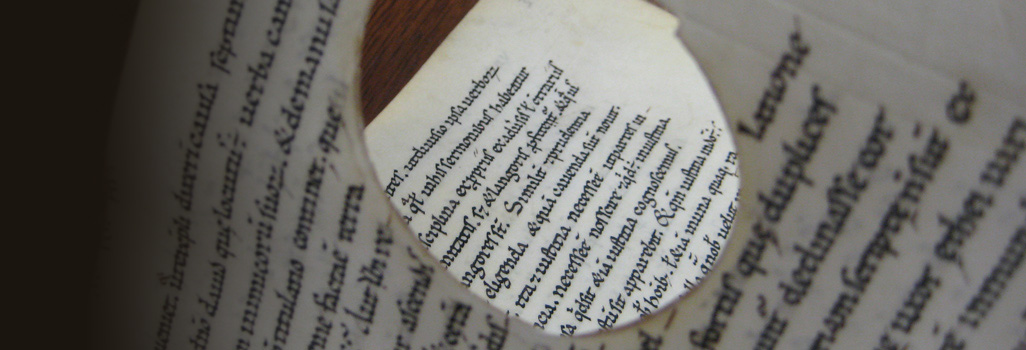

In my first Mellon Seminar I offered a close reading of Pacino di Bonaguida’s ‘Chiarito Tabernacle’ (c. 1340) that opened onto larger questions concerning the relationship between relief and “optical aesthetics,” both metaphorically and in practice. These questions revealed larger implications concerning the relationship between theologies of light, visual theory, and artistic practice and reception during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. In my second Mellon Seminar I expand on my initial findings to address how “optical aesthetics” and medieval art practice directly informed Leon Battista Alberti’s famous humanist account of painting in his De Pictura (1435). Tracing how concepts of “optical aesthetics” corresponded to medieval art theory, I will offer close readings of the artistic manuals beginning in the sixth century, including Theophilus (12th century), Cennino Cennini (late 14th century), and the Libellus ad faciendum colores (early 15th century). As a crucial component of this work, I elucidate the involution of the polyvalent Italian term rilievo, a key term in Alberti’s account of perspective, through its ancient (Greek and Latin) and medieval Latin predecessors. Previous etymological histories of rilievo have completely obfuscated its medieval origins in theological tracts and poetry by writers such as Nicole Oresme and Dante, instead focusing exclusively on Alberti’s recourse to ancient writers (primarily Pliny).

In my revisionist account of rilievo, I underscore the enigmatic nature of the term, both conceptually and in practice. In Alberti’s text, rilievo refers specifically to the painter’s practice of fashioning a two-dimensional figure or object to seem three-dimensional and naturalistic through shading and modeling. According to Alberti, the degree to which a figure or object stands out “in relief” is chief among the many foundations of correct painting using artificial perspective. A central claim of my project is that Alberti’s rilievo is more than just an appropriate metaphor gleaned from ancient authors to describe features of a new style of painting. Instead, I argue, the term referred to both actual medieval practices in which the true aspects of figures and objects were keyed to a beholder’s standpoint in the world and to medieval accounts of revelation, of the invisible becoming visible.