Seminar: “Habituating Knowledge in Late-Medieval Representations of Musical Time”

Philippa Ovenden (Mellon Fellow, PIMS)

In the first of four Questiones addressed to students of a late-fourteenth century Italian university, an anonymous author asks whether music is a science. He answers in the affirmative: music is a science, but it is also an art; it unites contemplative speculation and practical experience. Music is a habitus or mental habit, a permanent or habitual state of knowledge. Practicing music shapes the mind; the mind, shaped by the musical habitus, influences how a musician performs or thinks about music.

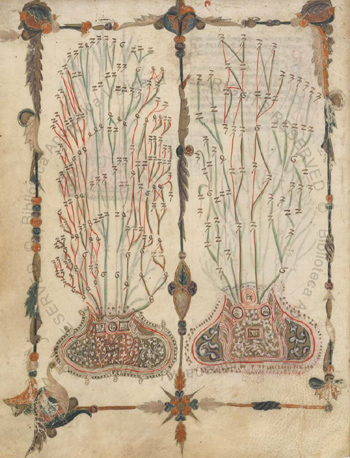

During the fourteenth century, interest in the mathematics of musical time was expressed through experimentation with the representation of rhythm in diagrams and notations. While much musicological scholarship has focused on the technical parameters of this phenomenon, contemporaneous theoretical accounts also address its philosophical significance. One of the most striking of these is found in Liber de musica (c. 1360s?) by the Italian theorist Johannes Vetulus de Anagnia, which describes an idiosyncratic method for the notation of complex rhythms using a series of theological symbols and six tree diagrams. A distinctive attribute of Vetulus’s diagrams is that, unlike contemporaneous models, notes are not represented directly on the tree branches. Instead, abstract durations of time measured in atoms are used to quantify different types of notes. Abstract temporal units—time spans that are not associated with any specific note shape—are also used to measure musical time in some of the experimental notations found in fourteenth- and early fifteenth-century Italian songbooks.

Tracing the use of abstract temporal units to measure musical time through a series of theoretical and practical examples reveals that similar conceptual precepts can act as the basis of notations that are formally or stylistically dissimilar. The application of the concept of abstract temporality in musical contexts, which began to be theorized in late-medieval angelology and is now taken for granted, underscores the relevance of both practical and speculative music to the development of ideas that continue to influence philosophical and scientific discourse.

Image: Johannes Vetulus de Anagnia, Liber de Musica. Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Barb. lat. 307, fol. 8v.