Seminar: “Physical, Psychological and Arithmetical Time in Johannes Vetulus de Anagnia’s Liber de musica”

Philippa Ovenden (Mellon Fellow, PIMS)

Since Apel’s classic monograph The Notation of Polyphonic Music 900–1600 (1949), the development of late-medieval mensural (rhythmic) notation has been characterized in terms of the opposition and mixing of French and Italian styles. While this approach is methodologically valuable, it allows only an incomplete picture of late-medieval notations to emerge. The emphasis that musicologists have placed on nationally-determined style has led little attention to be paid to music’s role in discussions that were of central importance to late-medieval thinkers, namely those that are today studied in departments of philosophy and theology.

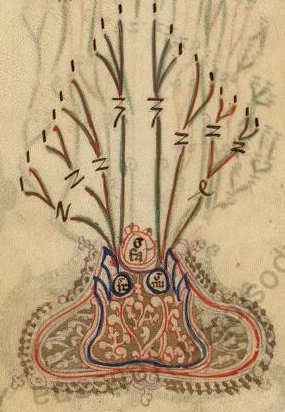

The neglect of the perceived extra-musical elements of music theory is particularly evident in literature on the work of the Italian theorist Johannes Vetulus de Anagnia (fl. c. 1350–1400). Author of a lengthy music treatise Liber de musica (The Book on Music), Vetulus sets out a system of musical divisions that is enriched by theological and philosophical symbols. Dismissed by previous scholarship as “rambling fantasies” (Hammond 1977), these symbols conversely provide authorial justification and mnemonics for an educated contemporaneous reader.

Following recent studies in the intellectual history of medieval music theory (Desmond 2018; Tanay 1999), this presentation traces a single concept in Vetulus’s work: time. While several music theorists appealed to the standard Aristotelian definition of time in their treatises, I illustrate that Vetulus used an Augustinian variant that emphasizes psychological experience of time. Vetulus follows this discussion by describing a temporal atom that is adapted from contemporaneous arithmetical teaching (computus). He uses this atom to measure the span of every musical note. Considering the treatment of physical, psychological, and arithmetical time in Vetulus’s work and that of his contemporaries reveals that some fourteenth-century music theorists adapted authoritative philosophical definitions to a musical context in order to reconcile the structures of physical sound and mathematical order.

Image: Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Barb. Lat. 307, fol. 8r. Tree diagram from Johannes Vetulus de Anagnia’s Liber de musica (c. 1350–1400)