Seminar: “The Bride and the Gift: Bridal vs. Political Gifts in 12th-c. Byzantium and Aquitaine”

Foteini Spingou (Mellon Fellow, PIMS)

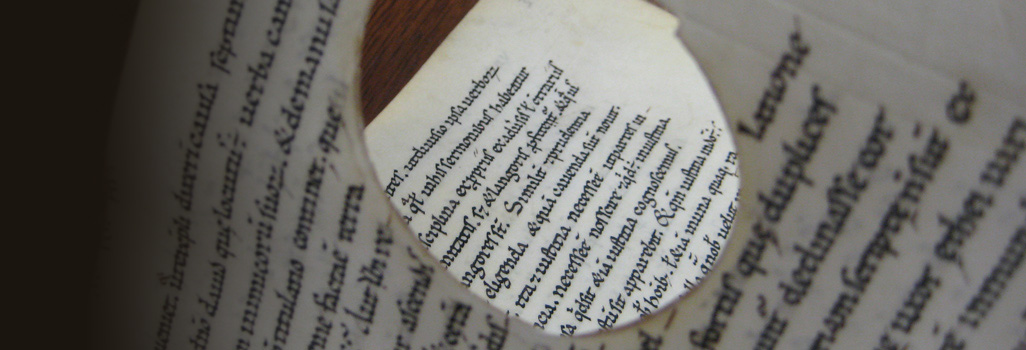

Weddings are known means of diplomacy in medieval times, but bridal gifts are a little-attested kind of diplomatic gifts. In 1161 and after the death of his first wife, Manuel I Komnenos (r. 1143- 1180) married to Mary, daughter of Raymond of Poitiers, Prince of Antioch. Shortly after their wedding, Mary offered to Manuel a provocative set of objects: a sword and a belt, which were reminiscent of the imperial military insignia. The objets d’art do not survive, but the poems attached on them have come down to us in a poetic anthology (MS Marc. gr. 524).

Not only the objects are unusual, but also their function as bridal gifts. The only attested bridal gift in Byzantium – others than those presented by Maria – come from the first wife of the same Manuel Komnenos. In 1146, Eirene-Bertha von Sulzbach, sister-in-law of Conrad III of Germany (1138- 1152), presented to her newly-wedded groom a gilded bowl adorned with precious stones. The function of this gift is made clear by the poem accompanying the bowl. According to the text, with this wedding (on the occasion of which the bowl was offered to the Byzantine Emperor) the Old and the New Rome are united. Crossing the borders of the Byzantine world to the East, a bridal gift is also attested in the French court: Eleanor of Aquitaine to Louis, later Louis VII of France. Eleanor presented a rock-cut crystal vase (the famous “Eleanor’s vase,” now in Louvre) to her husband shortly after their wedding in 1137. Eleanor had inherited this object from her grandfather, who had received it as a diplomatic gift from the last Muslim ruler of Saragossa. Eleanor by offering this object places Louis in his new role as Duke of Aquitaine. Intriguingly, Eleanor is known to held correspondence with Eirene-Bertha.

This presentation brings to light original evidence for the existence and use of “bridal” gifts in Byzantium. It argues for a possible western origin of the concept of such gifts, and its reuse in the Byzantine court as to march with the current cultural trends. It examines the objects involved to the gift-giving, as well as the logistics behind their creation (Who commissioned them? Why? and What was the role of the texts which accompany les objets d’art?). It further attempts to define these gifts (Are they diplomatic, political or bridal?), and it contextualizes their meaning in their contemporary sociopolitical circumstances. Above all, it is a cry for help in the path of defining this obnoxious gifts and find their place in Marcel Mauss’ “grammar of gifts.”